“Drawing inspiration: a series of interviews and prints made with movement mentors”

The following prints and interviews are the work that was my final Senior Study Project, Drawing inspiration: a series of interviews and prints made with movement mentors, for the Bachelor of Health, Arts and Sciences Program at Goddard College.

I have chosen to focus my final project on creating a series of interviews with white anti-racist mentors of mine as well as a series of lino cut prints inspired by these interviews. There are a total of 7 lino cut prints and 5 interviews. The purpose of this project is two-fold. First, I wanted to interview these 5 movement mentors in order to have conversations with them about what anti-racist organizing looks like to them in these current political times, as I have felt that there is a great need for guidance and lessons from people with more experience and decades longer involvement in the struggle. I also wanted to create some way of sharing out what these mentors shared with me to other people and groups of people in my community and beyond. Secondly, I wanted to create inspiring cultural work in order to share out these lessons and hopefully bolster movement morale.

This body of work is intended for anyone who considers themselves an activist, who is considering engaging with activism or is troubled by the times we are in both locally and globally. I chose to interview only white anti-racist mentors, despite the fact that so many of the movement mentors in my life are people of color, Black, and Indigenous, because I feel that my access to such mentors is rare. I do not know very many other white people who have had access to white anti-racist mentors in their lives, especially mentors who have decades of experience from various movements.

I wanted to hear from their perspective what they think younger activists need to be thinking about. What are the overarching lessons that older activists may have insights on, that I need to learn in order to be a more effective member of the various movements that I believe in? How can we learn from and thus not repeat the mistakes of those who have come before? What are the things, in my youthful naivete, that my elders would recommend I be thoughtful about?

I wanted to create this body of work in the service of our movement and it is my greatest hope that it can provide some insights, some learning, some inspiration and some hope in these challenging times.

Annie Banks, November 2017

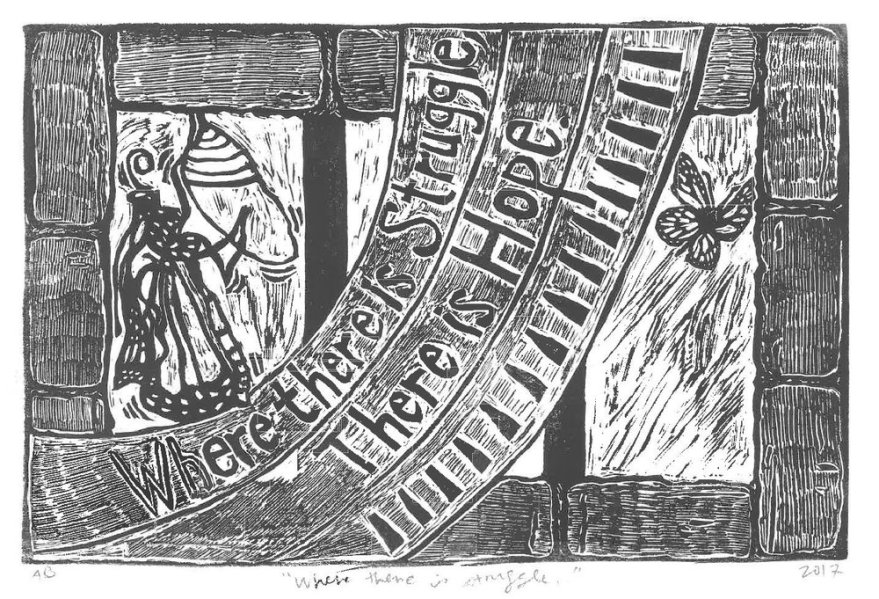

Artist’s statement for “Where there is struggle…”

Title: “Where there is struggle…”

Medium: Original linocut print, ink on paper, 8 x 10 inches

Artist: Annie Banks

Date: September 2017

This linocut was inspired by a conversation with my pen pal, political prisoner David Gilbert. David is currently incarcerated at the Wende Correctional Facility in upstate New York and I visited him in early September 2017. We talked about movement morale and how one maintains any hope in political times like the ones that we are currently in. David said to me, “Well, where there is struggle, there is hope” and his words resonated so deeply with me that I knew this phrase would be part of my first linocut of the series that I am making for my final project.

In doing some research on the phrase, it seems a common saying among activists and organizers, as well as having seemingly originated early on from a similar saying by Frederick Douglass. In his 1857 West India Emancipation address, he started it by saying, “If there is no struggle, there is no progress” (Douglass, 1857).

Sources:

Douglass, F. (1857). West India emancipation. [Speech]. From: http://www.blackpast.org/1857-frederick-douglass-if-there-no-struggle-there-no-progress)

Gilbert, D. (2017, September 1). Personal communication.

Interview #1: David Gilbert

Biography [from Certain Days]:

David Gilbert is a longtime anti-imperialist. He became active around the civil rights movement in 1960, and later organized against the Vietnam War. He spent 10 years as part of an underground resistance to imperialism. Working as an anti-racist ally of the Black Liberation Army in 1981, David and others were captured in connection with an attempted expropriation (theft for political reasons) of a Brink’s truck in Nyack, NY.

David was sentenced to 75 years to life and is currently being held at Wende Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison in New York State. In 1986, David became active as an advocate and educator around AIDS in prison after his codefendant Kuwasi Balagoon died suddenly of AIDS while still in custody.

He is the author of No Surrender: Writings from an Anti-Imperialist Political Prisoner (AK Press) as well as Love and Struggle: My Life in SDS, the Weather Underground and Beyond (PM Press) He is also the subject of a mini-documentary, “Lifetime of Struggle,” which is available from Freedom Archives (freedomarchives.org). He reprinted his 2014 calendar article as a pamphlet (featuring an interview with Bob Feldman), “Our Commitment Is to Our Communities: Mass Incarceration, Political Prisoners, and Building a Movement for Community-based Justice.” Kersplebeded also just published David’s booklet, “Looking at the U.S. White Working Class Historically”.

Write to David c/o:

David Gilbert #83-A-6158

Wende Correctional Facility

3040 Wende Road

Alden, New York 14004-1187

Question 1: Can you tell me about a particularly inspiring experience in anti-racist activism for you?

David Gilbert [DG]: My earliest inspiration came from seeing media coverage of the heroism of the civil rights movement – the 2/1/60 Greensboro lunch counter sit-in, the freedom riders (integrating interstate buses) attacked by howling mobs, Black people marching to register to vote getting set upon with police truncheons and dogs. These scenes not only gave lie to America’s claim of “freedom and justice for all,” but also showed a nobility of purpose way beyond anything I’d experienced in my white suburb and then at college.

But in terms of my own direct participation, the high point was the strike at Columbia University in the spring of 1968, when students seized 5 buildings and shut down that elite and (at that time) 99% white institution in solidarity with Harlem and Vietnam. I won’t attempt to tell the story of the strike; (for a good, brief account, see Dan Berger, Outlaws of America, pp. 47-52), but it was breathtaking to be part of something so large, militant and spirited.

The context for our actions was, of course, what was happening in the world. On 1/31/68 the Vietnamese launched the Tet Offensive, with attacks in almost every major city there, showing that the U.S. invasion would never subdue them. On 4/4/68 Martin Luther King Jr., was assassinated, and the response was Black uprisings in over 100 cities. These burning issues of the day had concrete expression locally, as the university was very much an institution integral to white supremacy and the war. In addition to it’s standing as a major slumlord, Columbia had recently moved to seize scarce public park land in Harlem in order to build a new university gym. People from the community would have access – to just 15% of it and only via a back door. Students who had been awakened by the civil rights movement began to ally with community opposition to the gym. At the same time, campus activists exposed how Columbia was conducting research to contribute to the U.S.’s criminal war.

The strike could be so successful only because of years of persistent organizing around both racism and the war, including a long train of requests, demonstrations demanding that Columbia end these travesties. Those efforts evoked only repression, which set off the strike. On 4/23/68 members of the Student Afro-American Society seized the first building; then other students took over 4 more. Four days later, the university called in the NYC police, who severely beat many protesters and arrested over 700. But the strikers never wavered, and the university never re-opened that semester.

Of course there was a kind of high from such strong and effective collective action and the culture of community and resistance that went with it. The inspiration was on several other levels, especially from shutting down an elite institution in solidarity with people of color within the U.S. and globally. That the cause combined Harlem and Vietnam helped us to understand that white supremacy at home and global domination are two aspects of one system. The support for the demands by a wide majority of students was based, in part, on the patient but persistent organizing over the preceding few years. The immediate issues showed how people will often become most engaged with local expression of the big, national and global, issues of the day. The Columbia strike also became inspiration for scores of other campuses to intensify their efforts against racism and the war.

Question 2: What would you say to younger, anti-racist activists in this political time and place?

DG: Let’s be frank, the forces of destruction in play today are frightening: multiple wars, global poverty, nuclear danger, environmental catastrophes-in-the-making. And, we’re up against a mega-powerful and super-ruthless ruling class. At the same time, our situation is far from hopeless: this system is inherently unstable; history takes many unpredictable twists and turns; the vast majority of humankind have a fundamental interest in revolutionary change. Given what’s at stake, there’s no choice but to struggle, as intelligently and persistently as we can. When we fight we have a chance to win.

While it’s only natural for those of us who care about people and nature to be angry at the wanton damage being done, anger is not enough to carry us through the long struggle ahead. We have to be fully conscious that our foundation is in identification with and love for the oppressed, the vast majority of humankind. That doesn’t mean romanticizing or overlooking problems, but it does mean that the needs and aspirations of the oppressed are always our basic reference points, the soil from which our resistance sprouts. At the same time as we prioritize programmatic work against the range of oppressions, we have to pay attention to how these forces play out within each of us and work open-heartedly to change that. We will face many discouraging moments, not only repression but also internal issues of ego, splits, even some betrayals. Throughout that we need to always stay grounded in that identification with and love for oppressed people, and the vision of the better world that’s possible.

Question 3: What is your greatest hope for the next generation of anti-racist activists?

DG: What I said in 2) above kind of frames my response here. It would be utopian to say that within a generation we can achieve a just society, where all human potential flourishes. But let’s hope/work for the oppressed to be making major strides toward reshaping the world in a humane and sustainable way, and that our efforts have helped large numbers of white people to rejoin the rest of humanity.

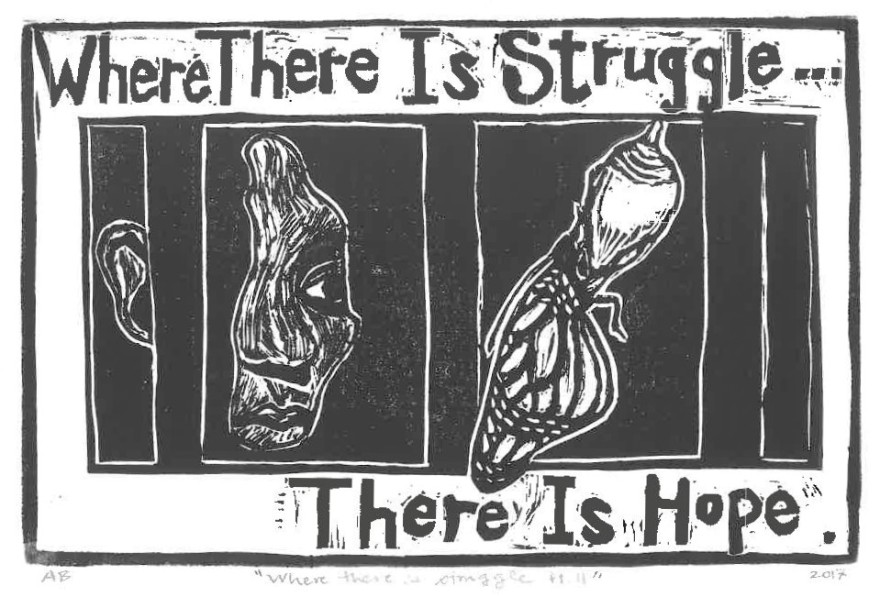

Artist’s statement for “Where there is struggle II”

Title: “Where there is struggle II”

Medium: Original linocut print, ink on paper, 4 x 6 inches

Artist: Annie Banks

Date: September 2017

After receiving feedback from my adviser on my first linocut for the phrase inspired by my conversation with David Gilbert, “Where there is struggle, there is hope,” I decided to make a second print featuring the same words.

I chose to feature a person’s face in response to the suggestion that this may encourage viewers to empathize more with the person behind bars. I chose to keep the original image of a butterfly emerging from it’s cocoon as I feel it represents the word “struggle” in David’s phrase – the butterfly, utterly transformed, fights for its’ freedom and will no doubt leave the confines of the prison.

I did not want to reify our societal images of who is in or who belongs in prison by choosing to use the image of a Black woman. I did so rather to show the reality of Black women still being unjustly incarcerated at twice the rate of white women (The Sentencing Project, 2015) as a result of the racist, sexist, homophobic and transphobic U.S. policing and prison systems.

My work with the California Coalition for Women Prisoners and other groups composed of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people and outside supporters has taught me that there are so many people inside and outside the walls who are fighting tirelessly for liberation. Onwards!

Sources:

Gilbert, D. (2017, September 1). Personal communication.

The Sentencing Project. (2015, November). Incarcerated women and girls. [Infographic]. From: http://www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Incarcerated-Women-and-Girls.pdf

Interview #2: Robert McBride

Biography:

Rob McBride’s political engagement began in high school with his opposition to McCarthyism and HUAC (the House Un-American Activities Committee) and support of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

He was further radicalized in the student movement of the 60s, especially in solidarity with the Black Liberation Movement and the Vietnamese war for liberation. He has combined political defense work with liberatory politics since the attacks on the Black Panther Party, on the American Indian Movement, on the Puerto Rican independence movement, and on war resisters.

He has worked with the Weather Underground, Prairie Fire, and Catalyst and brings personal experience with having loved ones imprisoned.

Question 1: Can you tell me about a particularly inspiring experience in anti-racist activism for you?

Robert McBride [RM]: One of the biggest inspirations was the victory of the Vietnamese over the US and that still resonates with me today. It was a long time coming, towards the end we knew they’d win but then seeing it, and seeing it so dramatic, was deeply inspiring. And it was inspiring, not only personally because I’d been so involved in opposing the war and supporting the Vietnamese, but of course we all knew that all these other comrades around the world were celebrating at the same time. So, I was in San Francisco then and we just turned out to the streets and had a very celebratory kind of march.

In terms of what’s more conventionally understood as anti-racism, I draw inspiration from the history. Recently reading a lot about Black Reconstruction and Black participation in the Civil War was very inspiring. [Also] visiting Harper’s Ferry […] was highly inspiring; I definitely recommend you do it. The park service has done a really good job of preserving and there’s a lot of good information about John Brown and his collaborators and the, I think it was called the firehouse, the small brick structure where Brown and his fellow soldiers made their last stand, that’s pretty completely preserved and it’s very simple. When we were there, there was a Black family visiting and they were ahead of us and they took off their shoes to go in. And we talked about what that meant in terms of hallowed ground. It made a big impression and yeah, it was inspiring.

That question also makes me think of all the questions going around about hope, as something that keeps people going. And I like to have hope whenever it comes up and I do, sometimes, but I do not feel that hope is necessary for political commitment. Mostly it’s just determination, rather than hope. The phrase that I have over my desk and that comes to mind all the time, is just simply, “Never give up”.

[…] Also, I was reading about Walter Benjamin [and] I think in one of Benjamin’s writings he says that, and he is speaking personally, that what drives people like him in terms of political commitment is not so much a vision of future of the society but rather horror at the crimes of the past. And that’s a lot true for me. It’s like, I don’t know what’s coming but I don’t want it to be like the past.

Question 2: What would you say to younger, anti-racist activists in this political time and place?

RM: Well, I wish that I had come up in a time when I could have found older mentors. I found a little bit of mentorship from a couple of professors at Dartmouth and from one in Madison but they weren’t really activists, I mean they were great people and I appreciated them but it wasn’t really mentoring and it’s true that we as a generation were arrogant, for sure, like coming up with that slogan [“Never trust someone over thirty”]. But we as anti-war and anti-racist activists were being denounced by practically all of the older Leftists, they were really angry at us and denouncing us for bringing NLF, Vietnamese flags to anti-war demonstrations, saying that that was inflammatory and that we couldn’t support communists, and of course, when we started breaking windows and things like that, they really denounced us… so it was not one-sided, that split between younger and older Leftists, and I think that our arrogance was in large in response to their criticizing of us.

One other thing which I see too much resistance to among many activists is travel. People need to travel. Very widely, anywhere, everywhere. We were told by our political leaders, white political anti-imperialist leaders, to not visit Puerto Rico, because we had to trust leader-to-leader communication between Puerto Rican leadership and solidarity leadership. As we got to know Puerto Rican comrades, they were shocked that that had ever been the line, even though so me of their own leaders had supported it, they hadn’t talked about it. And if you can visit and connect with friends and comrades, that’s the best, you get to see it. So, you know, we really need to build an international network of resistance and you can’t do that without travel. So I would say take time, make time, [and] it doesn’t have to be folded into an activist program. And of course, read, read, read, read, read, read.

I’ll tell you about one thing that bugs me, that I’ve been hearing from not especially younger comrades, I mean like comrades in their forties and fifties who say, we need a strategy, and that gives me chills because needing a strategy implies an organization leading it and coming up with it. We need strategy, we need strategic thinking, very much so, we need many people thinking about different strategies. I don’t think we need a party-led movement, I think we need a movement of movements. In terms of leadership, I certainly haven’t grasped it deeply enough but the Zapatista notion of leading from behind seems to me extremely important. It doesn’t translate immediately or easily into a white supremacist culture but nonetheless it’s really a different idea than the Leninist notion of leading from above.

Now that you’ve loosened me up, one other thing that I’ve been very late to recognize but I do want to share is that I think it’s important to extend our view, our critique, of society from a focus on capitalism to a focus on class society. When I say either one of those terms, I also mean their intersection with patriarchy and racism and colonialism but what I want to emphasize is that there is not a sharp distinction between feudalism and capitalism for example and you can go far back and the intersection of class, patriarchy, militarism, conquest, othering of those conquered is very familiar to today and influences us. So I think that should give us some patience about the process we’re involved in and some tolerance and many implications for strategy. So it’s not just about getting history right but if we see history as long and involved, it allows us to be better at figuring out what to do now and what do expect.

Question 3: What is your greatest hope for the next generation of anti-racist activists?

RM: Much, much, much deeper intersectionality. Some people have approached intersectionality in a kind of simplistic way that is just a Venn diagram but racism and patriarchy are fused at the very beginning and have been all the way through – and class and militarism. Militarism often gets separated out as like, the anti-war movement will go deal with that, but racism has always been militarist and patriarchy has always been militarist, integral, and the militarism is tied with conquest, so besides a problem of seeing intersectionality as additive oppressions, we have to go beyond class, race, gender to include colonialism and militarism and we have a very long ways to go in terms of understanding that. My own bent always is towards study groups, of course, but I think it will also be more effective if we can get artists and musicians to deal with it, but whatever people can do.

[M]usic reaches more people than books and that’s very important but music is also creative and so if you’re addressing problems with music you have to come up with a creative way of doing it – it’s about a more imaginative, a fuller, a different way of looking at the problems and looking at the steps to take. Recently, I’ve been learning how important the Blues have been in opposing white supremacy, starting in Mississippi at the overthrow of Reconstruction up through today and then how it’s spread into R&B, how it’s linked to jazz, and now of course, rap and hip hop, and so understanding that long history is important in music just as it is in straight politics.

The only other thought I have now about hoping for the future has to do with the importance of radical imagination. And that is something often overlooked, though I am very happy that young generations, younger than me, have more of that than my generation which reacted much more in a policy-oriented kind of way. You know, when we look at what victories have been accomplished, there’s been a lot of victory in creating a more radical imagination, you know whether that be Sun Ra in jazz or all of the writers that we love, etc.

Artist’s statement for “Even in hope’s absence…”

Title: “Even in hope’s absence…”

Medium: Original linocut print, ink on paper, 8 x 6 inches

Artist: Annie Banks

Date: October 2017

Inspired by my interview with Rob McBride, I created this image with the phrase, “Even in hope’s absence, we must be determined.” Rob spoke to me about how sometimes it is possible to have hope, but even in hope’s absence, there is another force – determination.

I chose to show a youthful, multi-racial and multi-gendered group of activists with a young Black woman central in the image, both as relief to the last print (which featured a Black woman in prison) and to show that activism is not a “white thing” but rather has always been led by the most impacted people closest to the contradictions of empire (Ellinger, 2017). Living where I do (Berkeley, California, on Ohlone territories) and growing up where I did (Victoria, BC, on Lkwungen and WSANEC territories), I have always seen that the vast majority of the leadership of justice movements comes from Indigenous people, Black people, and people of color, those most impacted, poor people, differently-abled people, women, and Two-spirit, queer, trans and gender-non-conforming people.

I chose to represent this group locking down with lock boxes to show their determination and also to uplift direct action as a response that “gets the goods”. Sometimes we must put our bodies on the line in the struggle for justice – and there is an incredible, long history of this, with more examples than I could ever possibly recount. What a powerful and beautiful legacy to be a part of.

Sources:

Ellinger, M. (2017, October 28). Personal communication.

McBride, R. (2017, October 11). Personal communication.

Interview #3: Donna Willmott

Biography: Donna Willmott is a member of Catalyst Project whose political roots are in the militant, anti-imperialist organizations of the 1960s, working to end the war in Vietnam, supporting Third World liberation movements at home and abroad, and challenging patriarchy in its many forms.

As a young activist, she was part of the Weather Underground Organization, and throughout her life has continued to work against white supremacy and in support of self-determination for Black people and other people of color.

Donna was incarcerated in the mid-90’s for activities in support of the Puerto Rican Independence movement and much of her organizing has focused on challenging state violence, supporting political prisoners and others subject to political repression.

Question 1: Can you tell me about a particularly inspiring experience in anti-racist activism for you?

Donna Willmott [DW]: I have been thinking about this question and one of the things that came to mind was the historic hunger strike in the California prisons in 2013, that was undertaken by prisoners to expose the conditions of solitary confinement,and to demand changes. There had been two other hunger strikes before then; the 2013 one was the biggest, some 30,000 prisoners participated in the early days of it. It was one of the most amazing organizing efforts that I have ever seen, and for white folks who participated supported the strikers I think it was a really transforming thing.

It was led by long-term prisoners in solitary confinement in the Secure Housing Units [SHU] – an incredible organizing effort by people living under the most draconian living conditions that you could imagine, where people are separated from other human beings, confined to a cell 23 and a half hours a day. Solitary is an attempt by the Department of Corrections to break people’s spirit, to keep them from organizing with each other, to try to stop radical, revolutionary organizing in the prisons; this is why the SHU was built. This hunger strike, called by radical Black and Brown prisoners as well as a progressive white prisoner, was historic for many reasons, the cross-racial unity being especially significant. On a human level, it was incredibly moving because of the sacrifice that people undertook to have their demands met – some people fasted for 60 days and were on the verge of dying.

I think it was a political earthquake in California because this reality that had been hidden from so many people was inescapable; it was in the public eye, people had to pay attention to it. The prisoners’ demands were in some ways quite minimal: eliminating group punishment, changing the criteria for classifying someone as a gang member, ending indefinite long-term solitary, providing adequate food, providing adequate programming. These were demands that could have easily been met by the Department of Corrections. But it took people to almost dying to shake the foundations around the whole program of solitary confinement.

For newer white folks who were in the beginning stages of anti-racist practice, supporting the strikers offered some challenges and some opportunities to shift their thinking. I think a lot of people are well-intentioned, they come to this work because they see these injustices and they want to help. But if you were going to be part of supporting this hunger strike, you had to accept terms that were different than a lot of ways people typically engage with support for prisoners. This was a self-determined struggle by people who had done decades in solitary. They developed a set of demands, despite their isolation, they were building unity inside, they were clearly in leadership of this, it was their struggle and there wasn’t anyone else who could tell them what was best to do. Imprisoned people were taking their destiny in their hands and saying “We are going to the wall for this”.

For people who were coming to support with a social-worker mentality, this really flipped the script. These were not victims, they had agency, this was self-determination. The terms of support and solidarity had to be based on respect for the leadership inside as well as their family members, mostly women of color on the outside working tirelessly to support the demands of their loved ones. So, I think it was a lesson to white folks to have some humility and remember that it’s not your place to try to set the terms for how people struggle.

So I think it’s just one of those important examples of the ways that people change in the process of struggle, when you’re actually out there, putting yourself in situations where you have to go through some changes yourself.

And I feel like it’s really important for white people who want to be anti-racist to find their stake in the struggle; you have to find why you’re there, you can’t do it for somebody else. I think the thing about the hunger strike was that it made people look at not only what is their government was doing, but why. Why did the state consider these people such a threat? Why did they find it necessary to isolate them, put them in the most inhumane conditions, under really torturous conditions? It made people look at our collective history, and it was an invitation to respond in a principled way to the leadership of people who were willing to give their lives to end this inhumane and torturous system.

It was one of the most moving things that I’ve ever been witness to and I think it changed a lot of people’s lives. I think some people look at it and say it was really the lawsuit that wound up releasing 1,600 people from solitary. And yes the lawsuit played a role, but it was the men, it was the struggle of the people inside that set the terms for this; there was no way you could avoid seeing that. You couldn’t just see it as a legal struggle.

Question 2: What would you say to younger, anti-racist activists in this political time and place?

DW: I think one of the biggest lessons for me in having been doing this work for all of my adult life – over 50 years – is believing in your heart and soul that this is a life-long struggle. There are so many things that we’re fighting against now that are the same things that I starting fighting when I was 18 years old. I think it’s easy to start to get cynical and say, “Well, we tried, we tried, we tried, and look around us – we haven’t won, or we’ve won a little bit but not enough.” But I think it’s essential to struggle against the discouragement and the cynicism, to believing that this is our life’s work. We may not see a lot of victories in our lifetime but it doesn’t mean that it’s not worth it, because we are part of a river of history. We are here because the people who came before us fought hard and we are here for the people who are coming after us, the ones that we will never meet. I see whatever we do as contributing to that forward motion in spite of the defeats and in spite of the setbacks, because this is how it goes. It’s such a part of US culture, and part of racial and class privilege, to want what we want when we want it, to expect immediate results. The struggle for social justice is not like that, so challenging some of those ideas is essential if we’re in this for the long haul.

And it’s important as a white anti-racist organizer to take a developmental approach to other white people and to understand the ways that it takes people a while to change. It’s not to say don’t challenge and don’t have high expectations but to also realize that none of us were born with these politics, someone taught us. I know in my life it’s mostly been people of color who taught me but it’s also been other white anti-racist organizers. I feel like it’s really important to not turn our backs on other white people and I think that’s a very common phenomenon in our movements. We see the racism and we see the effects of living in a white-settler colonial society and we’re repulsed by that. We often start to see ourselves as the good white people and so we want to dissociate from other white folks because of our own guilt and shame. I feel like one of the things that we are called to do as we are invited into this movement is to not leave other folks behind. To not see ourselves as a select few who are really the ones who are down for the struggle, but to envision a big, resistant, resilient movement. That means it’s going to be messy sometimes and it means that not everybody is going to come along with us but I think we need to be skilled about building principled alliances as part of a developmental process and giving people the room and the support to change.

In terms of this political moment, it’s really hard, it’s a really difficult moment politically. We are not the first ones to face really ugly forms of racism that have deep roots, historical roots, but the mask is off now and white supremacists feel very free and entitled to do what they’re going to do. We need to remember that this is not the first time, and people have always found ways to resist. Indigenous people have resisted genocide and are here and are fighting for their sovereignty and for their culture and for their sacred sites. People have survived fucking genocide, people have survived enslavement, people have found ways collectively to not just survive but to carve a path to liberation and we’re part of that, if we really respond with full hearts. We e are invited into a movement that will change our lives and will make us be part of a world-wide desire for something really different. It’s a long struggle and we don’t always get to set the terms of what it’s going to look like but in a certain way we don’t have a choice. We have to stand up to what’s happening and what’s being done in our name; once you say this is where my heart is, you have to keep going.

Question 3: What is your greatest hope for the next generation of anti-racist activists?

DW: I think that one of my greatest hopes is that the strategies that are developed are really rooted in our history. I think your generation has definitely made some advances – there’s such strong leadership from women and trans people of color that has really changed the the way that a lot of organizing happens. I feel like that’s an incredible strength and I think that’s something to nourish and build on, to really support and elevate that leadership because it’s also going to come under fierce attack. It has already and there’s going to be more of that.

I would say that also having an international perspective is one of my hopes for the next generation of activists. It’s not always a strength in the US movement, we tend to be border-bound in our thinking. Having a solid analysis of colonialism, of imperialism, that’s really the foundation of any successful strategy that emerges. We have to be part of actively promoting and defending the right to self-determination, that’s a bottom line. I ‘m not saying that if you win that and then everything else falls into place but I think it’s completely foundational. We have to look at the history of colonialism and white supremacy and grounding whatever we’re building for the future in a clear look at that history, understanding the ways that it plays out again and again and again.

Another thing that has been an advance in the last twenty or thirty years is a much more intersectional analysis. I think it’s very very important to understand the un-break-apart-ability of the struggle against patriarchy and the struggle against white supremacy and class struggle. Those things are totally bound up together. When I consider the reality that after 40 years of anti-colonial struggles in which people sacrificed so much there have been many failures and setbacks. Part of the failures were due to the strength of imperialism, but we have to look hard as well at the internal weaknesses, the failure to really address patriarchy and take seriously the liberation of women as foundational to a liberated society. I think about Nicaragua where the failure to incorporate the Indigenous and Black populations into their strategy meant real losses for their movement. Having a deeply intersectional analysis makes all the difference in terms of being able to chart a path to a fuller liberatory process. It’s not about being cynical, it’s not about “oh, they fought and they lost,” but it’s the idea that they fought, they won state power but there were real issues, they didn’t win their vision… yet. And I guess the key word is yet. It’s not over but we have to not be afraid to look at those [histories] and draw lessons and not romanticize what a revolutionary process is, because it’s not a straight line. It’s messy, we’re human, and we’re also living in a time of what I hope is a decline of empire but it’s not quite declining fast enough.

It’s a really difficult time and I feel like the basic questions of the survival of the planet, of what imperialism has done to the entire planet are critical.. And then there’s lots of hope, I think, or seeds of hope. There are people all around the world who are saying “Hell no!” and are giving everything they have to this, to build a different kind of world. And we have to be able to say to each other, “This is really freaking hard and that’s okay.”

[It’s so important to] have a sense of history, that we are part of historical movement that is, we’re part of a river of history. I think about both the looking back and the looking forward and the importance of radical imagination, the importance of holding on to a vision of what we think is possible, and really letting ourselves like go for it. To be able to say, “This is really the world that I want!” I want a world where everybody has their basic needs met, where everybody has food and clothing and shelter and clean water and clean air to breathe – and I also want us to have art and culture and creativity and joy and everybody should know how to dance and everybody should [laughs] know how to sing and drum and have a spiritual life., That’s like part of the world that we want to create, and we should all have our intellectual abilities cultivated and not feel like that’s just for a privileged few. It’s a human desire to think deeply, to reflect, and we have to create conditions where we can do that with each other. In this period where there is so much defending of what we’ve won, but if we get trapped in just a defensive posture, we’re sunk. We have to imagine the world that we want and imagine how what we’re doing today relates to that and that it’s not this far off dream. We have to dream big and be visionary, and all the steps we take everyday need to be aligned with that really radical, creative vision of what’s possible.

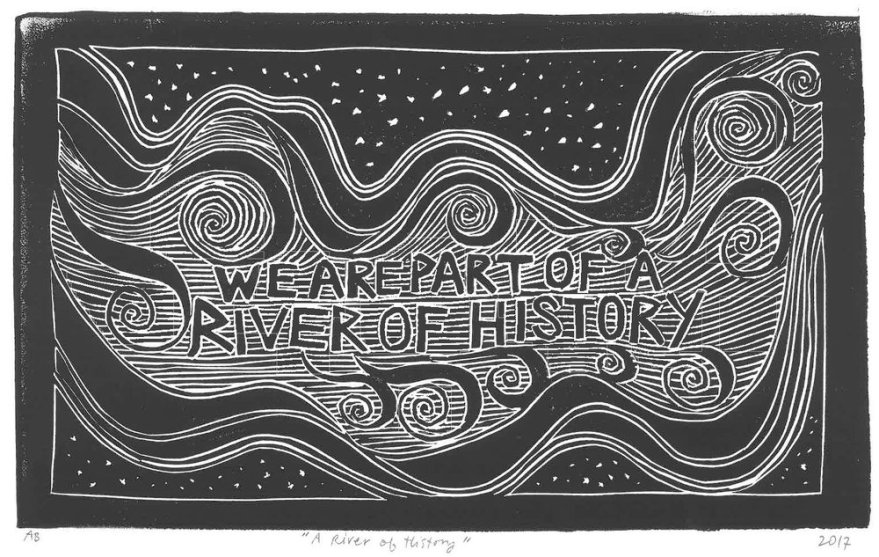

Title: “A river of history”

Medium: Original linocut print, ink on paper, 8 x 10 inches

Artist: Annie Banks

Date: October 2017

I created this linocut after my interview with Donna Willmott, where she used this phrase a few times. The minute that I heard her say it, I could feel the inspiration swell in my chest. To think of our movements as part of a greater river of history felt so powerful. It immediately makes me thinking of a number of things: the millions of people before us – and after us – we started and will continue struggles for justice, the immense power and also healing qualities of water, and the possibility inherent in reaching back and forward for connection and inspiration with our ancestors and our descendants.

Usually, I use photographs for reference with linocuts but this one I didn’t need to. It was like the image was already fully formed in my head. I just let it come out through my tools. I hoped that the rocks/stars along the edge of the river would also suggest that this could be an intergalactic river, like the Milky Way.

Sources:

Willmott, D. (2017, October 28). Personal communication.

Interview #4: Mickey Ellinger

Biography:

Mickey Ellinger is a long-time anti-racist activist from Texas. She was a member of the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee in the San Francisco Bay area in the 1980s and 1990s. She co-founded the Challenging White Supremacy workshop with Sharon Martinas in the 1990s. With photographer Scott Braley and Allensworth elder Mrs. Alice Royal she wrote a book on the utopian Black community of Allensworth in the California Central Valley. She works with Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival supporting workshops to revitalize California Native languages. She is currently working on a book about City College of San Francisco resisting corporate education “reform.”

Question 1: Can you tell me about a particularly inspiring experience in anti-racist activism for you?

Mickey Ellinger [ME]: I was raised by anti-racist parents, which is unusual for a white person. I was raised in the south, Texas, not the deep south, but it means that in some ways I had some short cuts. I was a moral anti-racist all my life, [in] family experiences, family training. I went to college right as the sit-ins began, so the direct inspiration were the sit-ins in the south and we did sit-ins in Austin, y’know, we saw ourselves as part of the Civil Rights Movement very, very early. It was a moral stand.

When talking about it last night, I realized that probably a more telling experience was a challenge I did not rise to which was Freedom Summer in 1964. I had no intention of going south, I was terrified of the whole idea, I thought those yankee white kids were nuts and I felt bad about it. And so in the fall of 1964 when Mario Savio and Jack Weinberg [Berkeley students arrested for tabling at U of Berkeley campus to educate other students about the Civil Rights Movement] and people who had been in the south were on the Berkeley campus and the so-called Free Speech Movement, which was all about defending the Civil Rights movement and defending the Civil Rights movement in the south, I felt compelled to show up and do something. And at that point it was guilt, I felt bad about being too chicken to have gone south. That would have been ’64, with the war, the convergence of the Vietnam war and the Black struggle, then internationalism through the war, anti-imperialism, Black liberation, so then seeing opposing white supremacy as a political task was somewhere in that later 66-67 period and was very liberating because it wasn’t about making amends or atoning for my weaknesses, it was a way forward.

We’re talking overthrowing the system here so then you think, well how do we do that? And that’s when the centrality of internal colonialism … [you ask] is that sort of the lynch pin of it? If you begin to think so then your opposition to white supremacy and your revolutionary determination all take you down the same path. More or less, mostly.

[Then there’s t]he thing about collective study and organization and action that means that what you individually do well and badly gets evaluated collectively, well and badly, but the chances of seeing a way out of a predicament are improved profoundly because there’s the qualitative difference between, “Am I a good person or a bad person?” and “Is what I’m doing helpful or not helpful?,” in a collective setting. The collective setting, done in a helpful way, sort of stipulates you’re a good person, otherwise you wouldn’t be looking to do this.

Question 2: What would you say to younger, anti-racist activists in this political time and place?

ME: Another world is possible. That slogan is about defeating ideological hegemony. It also is about sort of where we are. We have to have a vision of what’s possible, we have to take some risks for it, we have to organize for it, we have to understand what white people can do, what they can’t do. What following Black and Brown leadership looks like, which is not doing everything that some Black person tells us, not because they are the most oppressed but because of their location in the whole empire, and also because it’s right, of course. The thing about ideological hegemony is this belief that it can’t be otherwise. Then you either conform or you act out in desperation and neither of them is transformative. And part of what is so hard about now is it looks very dark out there.

We can’t will a revolutionary situation into existence. We can see what’s moving here and what’s moving here and we can have ideas about what to support and what to take on and how to work with white people. We’ve only got 24 hours in a day, so what’s the most useful thing to do now? And it’s a very long road and we have to have a pace that means we can keep doing it and not look for shortcuts.

The other thing that I am very interested in right now – with this “Me Too” moment right now – well, patriarchy is very old and very deep [and I think] it’s possible that some of this outrage could be part of a real struggle for liberation. If we quit hating other women, who aren’t as bold as we are, if we quit being contemptuous of them as well in addition to being angry at male supremacy… I think it’s just very very interesting and full of land mines, so that’s my opening thought about now. Another world is possible, in spite of everything, that would be my mantra.

And organization, again, not because it’s the path to certainty but because it gives you some place to try to work it out. I think, especially in terms of breaking with ideological hegemony, that’s the job of a culture. I’m not talking about it’s political line, exactly. I’m talking about the ability to be with other people trying to engage in that project and to help each other out because you know you can begin to get a little collective body of knowledge.

We were all raised patriots, whether it was salute the flag patriotism or we didn’t pay any attention to it but the idea that the United States was engaged in a wrong war, that was overthrowing the dominant ideology, that was huge and it was earth-shaking individually so to have an anti-war movement was really essential because we all went home for Thanksgiving and had screaming fights with our families and walked out of the room over it. [Due to] the subtlety of the white supremacist hegemony, it’s really important to have some collective approach to defeating it because you have to have some way to think about what’s actually changing people’s minds. We need a lot of help if that’s our job, and we need each other’s help. And we need a very complicated, principled set of relationships with organizations led by people of color. And while it’s not their job to educate us, on the other hand, they’re stuck with it. And we have to figure out how make it worth people’s time.

[Also] people have to feel capable. Part of the thing about hegemony, it covers despair, it’s both a cop out and a comfort, “there’s nothing I can do, there’s nothing I can do”. But if there is something you can do and you actually did something, well then, what else might you do? So, that’s why we organize, that’s why we do campaigns, that’s why you say “let’s defeat this terrible thing on the ballot, let’s elect…”, etc., to give people a sense that we can make something happen. So, I think that’s the question right now, what can we make happen?

And, we take care of things. We repair what we can, we take care of things. We are kind of in a lot of trouble as a planet, we’re really running out of stuff, and we have to take care of what we’ve got and we have to fix some stuff. It’s a darker time. When we were younger, we were very angry but I think the sense of what was possible was really different than what is possible today. The state of the planet is … I don’t quite know how to finish that sentence, but… I don’t like it.

Question 3: What is your greatest hope for the next generation of anti-racist activists?

ME: I think reconstructing community and the commons is really important. Neo-liberalism, both in practice and in ideology, is so individualized and atomized and that effects us all, including our movements.

I’m very hopeful about the unsettling effects of fighting patriarchy, actually. If attacking patriarchy and white supremacy could end up looking like an assault on all forms of domination, that would not be a bad thing. I think what’s important, particularly in the United States, about white people being anti-racist activists is that that’s the sort of lynch pin of the particular form that domination has taken in the United States. It’s particularly powerful and it’s the obstacle to unity. But it’s the domination that’s the problem, because peace and justice have to be served in a setting where everybody is equally valued, that kind of egalitarianism not that we’re all the same but that people have equal value in the world.

I think there’s a vision in [intersectionality] that is really valuable, that is really valuing every person’s participation, decolonizing this way of thinking, changing this pattern of behavior in the service of seeing all forms of domination.

The one that I laugh at myself is, you know I spend a lot of time with kids and I think I’m good with kids and then I started listening to myself about how much I said to them was “No” and “Stop it” and tried to see what would happen if I consciously really tried to say, on the other hand, is there another way to do it that isn’t “No” and “Stop that” because it’s about power. And sometimes it’s yes and sometimes it’s no, but to just to really think about what the world would like look, a world where we’d overturned the forms of domination, where we did it differently.

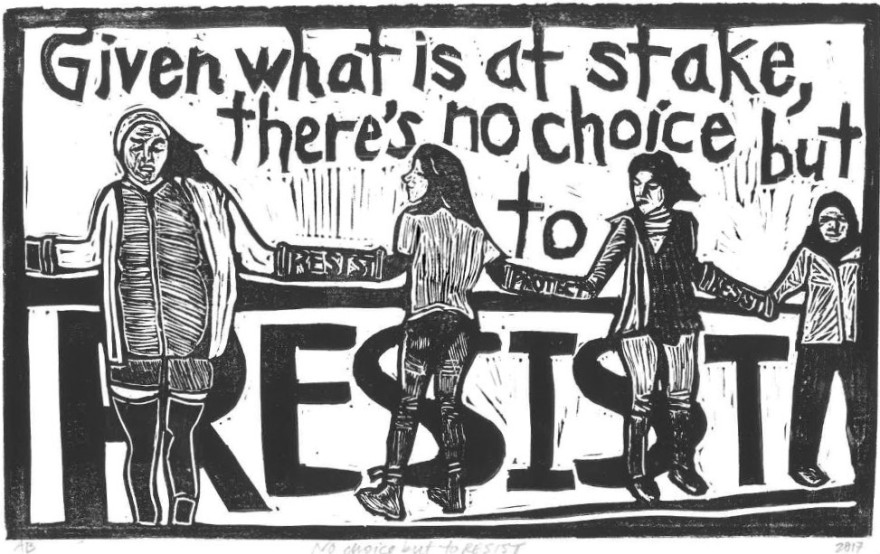

Title: “Given what is at stake”

Medium: Original linocut print, ink on paper, 8 x 10 inches

Artist: Annie Banks

Date: October 2017

This seems a most fitting post, the night before both the #J20 defendants in DC and the #BlackPride4 are set to go to trial, on November 20, 2017. #DropTheCharges #DefendJ20 #FreeTheBlackPride4 #DropJ20

This phrase is another that comes from David Gilbert, in his written responses to my interview questions. He used the word “struggle” originally but I decided to use “resist” because of its resonance with the current fight to drop charges against J20 defendants. Myself and ten comrades are also part of this fight to drop the charges – while we are not facing felonies, we are going to court for criminal misdemeanors, with a potential trial starting in March 2018.

I wanted to create a piece of work to uplift my comrades and to inspire us as a group. I wanted to use this opportunity to focus time and energy on printmaking to create something useful and meaningful for my comrades. I also wanted to take time to celebrate our resistance, especially since we need to remain rooted in our intentions as we enter into a potentially difficult trial process.

For more on how to support J20 Resisters locally and nationally, please join our Facebook group (“Friends of J20 Resisters”) and check out the national updates on http://defendj20resistance.org/.

Sources:

Gilbert, D. (2017, October 31). Personal communication.

Interview #5: Anonymous

Question 1: Can you tell me about a particularly inspiring experience in anti-racist activism for you?

Anon [A]: I grew up in a little town, white town, no [people of color] at all. There were Black people and other folks thirty miles away, they came to work at the big plants, but they left town at the end of the day. I didn’t even know there were people of color working there. And I didn’t come to an anti-racist position until much, much later. I started to make a list of conceptions that I came to as I started to understand the world and opposing white supremacy was actually number ten on this list. So it was: the war against Vietnam is wrong; the US was corrupt and should lose; the US should be defeated; there were colonies of imperialism; the US is imperialist; there were internal colonies; only if those colonies were free could there be actual transformation; we had a choice to either stand with imperialism or stand with the people of the world; support the liberation of Black people, Puerto Rico, Mexicans, etc. and then, we had to oppose white supremacy. So it was kind of a long-ish road and it wasn’t all as clean as that but when I started to look at it, I realized that I don’t think I saw the struggle against white supremacy as a particular personal stand until much later and actually until I had already screwed up many times personally and politically many times around white supremacy.

[There are] places where I did things that I really regret how I acted and that was part of what I wanted to say to people who are coming into this. You will make mistakes. And some of them will be cringe-worthy and some will be really bad and something you have to think about is that you will make those mistakes and you have to have to be part of some kind of organization you’re responsible to because otherwise it’s very difficult to pick yourself up from those mistakes. Without organization, what you do is you avoid the struggle and you back off and you avoid places where contradictions will come up. And it isn’t that every time that you are criticized you will be totally in the wrong but you have to recover from the places you really did fuck up and so it’s important to have people that you’re responsible to that will help you recover from that and go back into the struggle.

And I did come up with what I thought was an inspiring experience – it was a couple of months ago when three or four thousand people came down to the Berkeley Civic Center when the fascists tried to have a rally. People were really there to oppose white supremacy; that was on all the signs, it was totally cool. Hopefully, they will come out many times. But that really was inspiring, to see those folks come out and do that.

Question 2: What would you say to younger, anti-racist activists in this political time and place?

A: I guess I would say another world is possible but it’s not guaranteed. There’s a lot of mistakes to be made and one of the key things that people have to understand is that we don’t have to be pawns of imperialism, we don’t have to be pawns of racism, we don’t have to be pawns of male supremacy. Once you look at that, it opens up a whole new, different set of things to work with and to look at. It’s one of the reasons that I think that a lot of people are reluctant to look at harsh reality because they realize that once they give a little bit on one conception then a lot of things follow and they might have to do something. Their lives might be changed because they changed their mind and, so a lot of people get very dug in on keeping things the way they are.

Obviously part of what everybody will say is that we have to go out and talk to white people and break some of this loose. And I think that’s true and I think that’s really difficult. The people who decide to go move back to Michigan or Tennessee or whatever, I have huge props for them, great admiration. At this point in my life, it’s not something I am going to do, nor am I going to join any clandestine organizations again. So, I’m glad of that but I think there are still plenty of places where we’re going to have to make choices that are going to be difficult.

I would also say, go ahead and be open. Try it on, take a look at it, if it isn’t what you think, if it doesn’t sound true, you can go back to wherever you were but try it on, look at a different view and see if it helps you understand how the world is and gives you a handle to do something about it. So to a certain extent that is a leap of faith and I think that all of us have to do it and I would say the times I regret most are the times that I felt I didn’t rise to the occasion – there are plenty – and there are some times when I felt like, despite being terrified, I did rise to the occasion.

It’s difficult, to look at decisions not based in fear. I think it’s important in a lot of cases to look at this and ask ourselves, is this fear talking? If it is, how can I deal with it? Is this really something I should do because it’s right or is this something I won’t do because I’m afraid or is it something I want to do because I don’t want to look like I am afraid. And I think that happens too, like it did for me. I have struggled with some of my younger friends, I think they sometimes do things so that they can demonstrate to themselves that they are getting past their fear and then I think a lot of people my age, it’s a big struggle because they give in to their fear and they don’t want to take another choice that would be a – might be icky, might be difficult, and it might be a bad choice. I have friends who have spent and who still are spending, a great deal of time in prison for the choices they made and that’s really rough but there aren’t any guarantees on that. Another world is possible, but you personally may not do so well within it.

[On the importance of cultural work], one of the things that got me through high school was music, particularly jazz and we lived in this little white town, there was essentially no jazz except what we made so we had to go out and get records and go to other cities and that was really important for my entire crew and not just me. And then when I went into [the] Weather [Underground Organization], in the early days we tended to downplay cultural work. We said that what matters is going out there and kicking butt and cultural work was secondary. In the last while, I’ve come to appreciate cultural work a lot more both because I like doing things myself and also because I see that how change happens is a lot guided by what the underlying cultural changes are. So, if people value interesting music, if people value revolutionary art or even just really cool art, it changes the situation and changes everybody’s attitude. I think it’s really important. And I wish we had some more stuff up on the streets about the fascists. We need this because, while we certainly have some groups of people that are willing to duke it out with the nazis, I think what we most need at this point is another fifteen to twenty thousand people who are totally hostile every time they show up. Fascists are hanging out in bars in Berkeley and there aren’t enough people harassing them. So, yeah, we need some [art] on the streets and some music that reinforces revolutionary thought.

Lastly, I would add [that we have to] try to take care of each other. I didn’t use to think of that as much as a priority. I used to think that everyone would take care of themselves and it would all be okay, back when I was in Weather and the WUO and places like that. Sometimes we didn’t take care of each other so much. There were certainly people who did much better than I did but as an organization, it wasn’t necessarily that well done. It wasn’t until I got to working with the anti-repression committee in Occupy, which was almost completely made up of women, that I was in a place where I felt like people were really watching after each other, and still struggling over issues. I think that’s not as common in our political circles and it’s really important.

Along with that, I would also say push yourself to do as much as you can but don’t believe that you’re that much better than everybody else because you do it. I think a lot in our younger days and certainly I see it happening now. Sometimes the people who are the most bad-ass are the ones who think we should get to define what the struggle is. In reality, however, there’s not just one way to make a revolution and we should be very careful not to think that we have the best or only belief system. That [way of thinking] is pretty corrosive.

Title: “When we fight”

Medium: Original linocut print, ink on paper, 8.5 x 14 inches

Artist: Annie Banks

Date: October 2017

I created this linocut based on a photograph of the spokesperson and host of Unist’ot’en Camp, Freda Huson. The phrase comes again from David Gilbert and I chose to use it in conjunction with an image of Freda because she is someone who has truly taught me through her actions that this phrase is true.

As spokesperson and host of Unist’ot’en Camp, she has been part of a movement to create Indigenous homesteads that protect territory and culture and oppose pipelines and other destructive, extractive industries. The camp has stood for almost 8 years, in the direct line of proposed pipelines and the fight that the hosts, the Unist’ot’en clan and the thousands of supporters have put up over the last near-decade has had global ripple effects. All because the Unist’ot’en decided to fight.

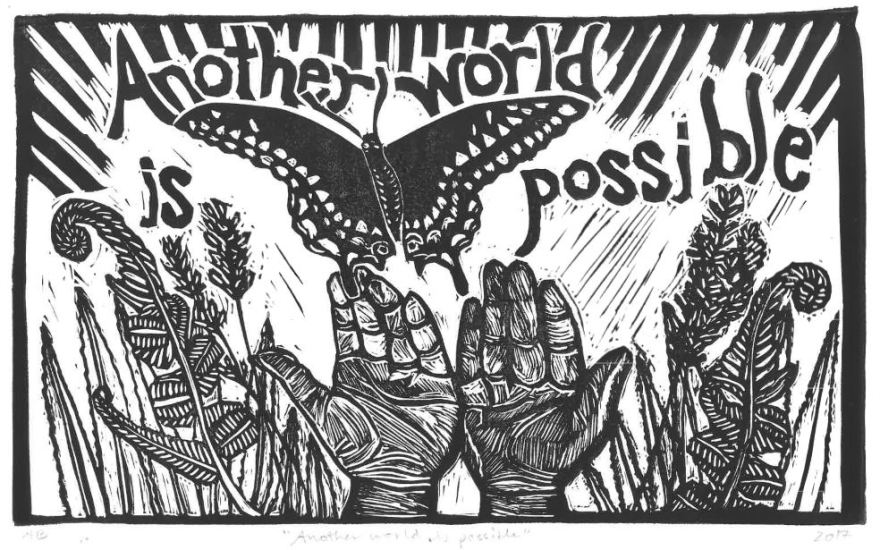

Title: “Another world is possible”

Medium: Original linocut print, ink on paper, 8.5 x 14 inches

Artist: Annie Banks

Date: November 2017

The final print in the series is inspired by my interview with Mickey Ellinger, who said this phrase a number of times as we spoke – with the caveat that this “another-world” will need to be envisioned, organized for, fought for and protected. Another way to look at it would be, as Mickey said to me, “Another world is possible – but it’s not guaranteed” (Ellinger, M. Personal communication. October 29, 2017). What are we doing or what will we do to make sure this another-world can emerge?

I chose to show a child’s hands releasing a Black Swallowtail Butterfly to represent the next generations that will be part of this world. The butterfly, a classic image used in many campaigns for migrant justice as well as artwork relating to prisons and freedom from incarceration, is a recurring theme in my work because these struggles are important to me and often on my mind. What would a world where everyone is free, as free as this butterfly, look like?